Lupus, Fatigue and Lifestyle

This site is intended for healthcare professionals as a useful source of information on the diagnosis, treatment and support of patients with lupus and related connective tissue diseases.

Introduction

Whilst some symptoms of lupus, such a rashes, hair loss and joint swelling are physically obvious, it is often the unseen effects of the disease that have the most significant impact upon an individual’s life. The effect of symptoms such as fatigue and depression reduce quality of life and diminish daily function. It is, therefore, vital that fatigue is considered when reviewing any patient with lupus in both primary and secondary care.Fatigue

Fatigue is commonly reported by patients with lupus and results in significant disruption to activities of daily living and reduced quality of life. Between 80-90% of patients report fatigue to be the single most debilitating symptom of their disease. This troublesome symptom represents a significant challenge to both patients and clinicians alike. Previous studies have found that fatigue levels do not typically correlate with markers of disease activity. Furthermore, patients with otherwise well controlled disease (with little in the way of clinical or serological active disease) continue to be troubled by persisting fatigue. This problem is further compounded by the fact that increasing immunosuppressive treatment often has little benefit to an individual’s fatigue. This troublesome symptom has wide reaching effects on lifestyle with associated impairment in function due to reduced concentration and difficulty with both exercise and work.Causes of fatigue

Fatigue may arise from a combination of factors that may act singly or simultaneously. These include:• Active SLE

• Hormonal and metabolic factors (e.g. hypothyroidism and vitamin D deficiency)

• Anaemia

• Sleep disturbance

• Fibromyalgia

• Medication side-effects

Although fatigue does not always correlate with disease activity, it is important to start by assessing the patient for evidence of lupus disease flare. It is, therefore, important to enquire about any new joint pains, oral ulcers or hair loss that may support the diagnosis of a lupus flare.

In the absence of active SLE, common metabolic disturbances should be considered in all cases. Intercurrent thyroid disorders commonly occur in patients with lupus, with studies suggesting that there is a three-fold increase in the incidence of hypothyroidism compared to the healthy population level. Similarly, anaemia is frequently seen and may be directly the result of the disease (in the case of

haemolysis). Drug therapy may also be a potential cause for anaemia, particularly

in view of frequently seen gastric side effects of medication such as non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and steroids. A number of studies have also noted associations between low vitamin D levels and fatigue. It is, therefore, important that all patients with lupus who report fatigue are screened for anaemia, hypothyroidism and vitamin D deficiency in order to identify a potentially easily correctable cause.

Unfortunately, in many cases the cause of a patient’s fatigue is not easily explained by an underlying metabolic disturbance and so can be more challenging to manage. It is important to consider that, as with many autoimmune rheumatic disorders, patients with lupus frequently describe difficulty getting to sleep. In addition, up to two thirds of patients report either poor sleep quality or early wakening. Sleep can also be significantly disrupted by pain, which has previously been shown to correlate closely with fatigue levels. Pain in lupus may be the result of either active disease (for example due to arthralgia or arthritis) or due to intercurrent fibromyalgia (which is more commonly seen in lupus than in the general population). Nocturnal respiratory symptoms and restless leg symptoms have also been identified as potential reasons for disturbed sleep in lupus.

Medication is another key factor that should be considered when trying to address why a patient may be troubled by fatigue. Corticosteroids (that are commonly used in the treatment of lupus) have been shown to result in significant sleep disturbance and may also contribute to exacerbate fatigue. In addition, opiatebased analgesia, antidepressants and anxiolytic drugs frequently contribute to fatigue and should be discontinued where possible. Although unlikely to be the only causes of fatigue, a careful review and rationalisation of medication is, therefore, required in any patient with lupus suffering from fatigue.

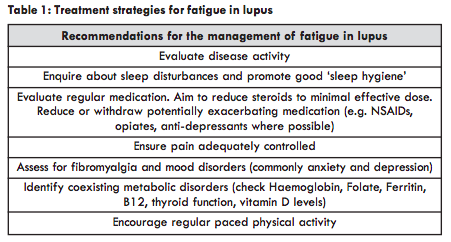

Treatment of fatigue

As has already been highlighted, increasing immunosuppressive or steroid therapy offer little benefit with regards to fatigue levels. Many recent trials assessing for the efficacy of novel therapies in the management of lupus now include quality of life scores (including fatigue) routinely as an outcome measure. In the BLISS Trial, investigating the efficacy of belimumab (the most recently licensed new therapy for the treatment of lupus), fatigue was noted to improve as a secondary outcome in those receiving the drug. This suggests that belimumab may potentially alleviate fatigue although NICE Guidance limits the use of this drug to only those with highly active disease. Given that many patients with fatigue are in either remission or low disease activity then belimumab cannot be used routinely in the treatment of fatigue. Studies have been conducted to assess the efficacy of other therapeutic options in the treatment of fatigue. Vitamin D deficiency has already been mentioned as a common metabolic disorder seen in many patients with lupus. This may be partially due to reduced production in the skin because patients with SLE are advised to avoid the sun and apply high factor sun protection given that ultraviolet radiation can result in a flare of classical skin symptoms or a more generalised lupus flare. Although this may not be the primary cause of fatigue, it is likely to exacerbate underlying tiredness and it is, therefore, important to check vitamin D levels and ensure patients receive adequate replacement (Table 1). In a previous blinded study of weekly high dose vitamin D supplementation in the context of juvenile lupus, both improved disease activity and fatigue levels were noted in patients receiving vitamin D supplementation compared with placebo control.Given the lack of evidence to support pharmacological treatment of fatigue in lupus there has been an increased focus on non-pharmacological options. Previous trials of graded exercise have shown significant improvements in fatigue levels after 12 weeks. However, it is important to remember that the benefits to fatigue are only maintained if the regular exercise regime is continued. In cases where physical activity is discontinued following participation in the study, fatigue levels deteriorated again. Encouraging patients to participate in regular physical activity whilst troubled by high levels of debilitating fatigue is, however, challenging.

Mood

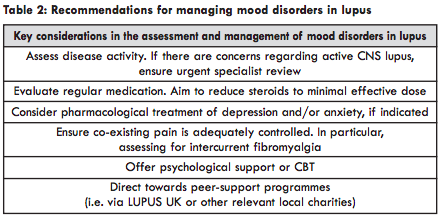

Mood disorders are an important consideration when assessing patients with lupus. The precise burden of poor mental health in lupus is difficult to quantify, with previous studies showing mental health problems to affect between 13-60% of patients. Intercurrent mood disorders are attributed to active lupus in less than half of cases. Depression, anxiety and psychosis can all be symptoms of neuropsychiatric lupus that can be difficult to diagnosis and differentiate from alternate causes. However, this form of the disease is rare and seldomly seen in those who have been diagnosed with lupus for more than five years. If there is a suspicion of active central nervous system (CNS) lupus then specialist input is required. Brain imaging does not show specific diagnostic signs of CNS lupus but can be used to exclude other diseases that cause similar symptoms. Often detailed examination of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is required to make a diagnosis of CNS lupus and can be helpful in ruling out other possible causes such as infection.In terms of medication, corticosteroids are widely documented to cause a number of psychological side-effects with the most well-known being psychosis. However, in the context of lupus this is rarely seen although should be considered in the event of new symptoms (such as hallucinations or delusions) in those who have either recently started steroids or have had their baseline dose significantly increased.

Previous studies have shown a number of key psychosocial factors that play a role in the mental health of those with lupus. Depression has been noted to correlate closely with both pain and fatigue levels (however, it is difficult to differentiate exactly whether there is a bidirectional nature to this relationship). Furthermore, lupus, like many other chronic conditions, is associated with various adverse effects on mental health. Community based psychological support has been shown to benefit patients and should be offered to all patients reporting symptoms of anxiety and depression (Table 2). Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), and peer support in particular, have also previously been shown to be beneficial in terms of improving mental health in patients with lupus.

Diet and Exercise

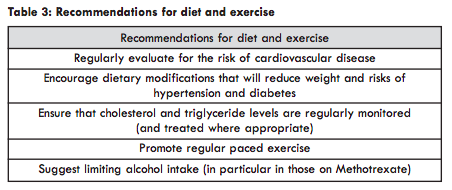

Questions relating to diet are commonly raised by patients attending lupus clinics and are often centred on the role of elimination diets (i.e. reducing or entirely cutting out food groups) and supplementation (for example, taking additional nutritional supplements that can include vitamins). A recent online survey found that patients are keen to understand if there is a role for dietary modulation as a treatment of lupus, with many patients suggesting that they would be keen to make dietary changes if they felt that it would improve their symptoms. Currently, there is little robust evidence to suggest that any type of diet has a measurable effect on disease activity although work in this area is ongoing.Given the increased incidence of cardiovascular disease in lupus, the majority of dietary advice centres on reducing this risk. Patients are advised to adhere to a low cholesterol diet and limit their intake of sugar so as to reduce the risk of diabetes. Maintaining a healthy weight is important for not only reducing the risk of atherosclerosis but it has also been suggested that obesity results in increased serum cytokine levels that may in turn exacerbate lupus disease activity. Anaemia has already been highlighted as a potential cause of fatigue and is prevalent in many patients with lupus. It is, therefore, important to promote a diet that sufficiently provides enough key vitamins and minerals; including B12, folate and iron. Current advice given to patients when the question of diet is raised is the promotion of a Mediterranean diet, rich in vegetables, fruits, nuts, grains and fish (with limited meat consumption). This has previously been demonstrated to be beneficial in the management of obesity and conferring a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease.

Regular exercise is important in reducing the risk of atherosclerosis and, as has already been mentioned, can alleviate other troublesome symptoms such as fatigue. Although pain and fatigue can be significant barriers to regular exercise, it is important that a regular physical routine is promoted in all patients. Where patients have not previously been participating in any regular exercise it is important to promote pacing as over-exercise in the first instance can exacerbate joint/muscle pain and fatigue.

With regards to alcohol consumption (Table 3), it is important to remember that some treatments for lupus are metabolised by the liver (such as methotrexate) and in these cases it is important that alcohol intake is kept to a minimum.

Work

As is the case with many chronic diseases, lupus can have significant implications on an individual’s work life. Understandably, many patients will see remaining in work a key goal and the ability to continue with work is a frequently asked question, in particular at the time of diagnosis. Aside from the obvious financial benefit of work, continuing in a job also plays an important role in an individual’s source of self-identity. The potential perceived risk of losing employment can also either cause or exacerbate underlying depression and anxiety. A number of key barriers can limit an individual from working; including fatigue, pain, depression and the need to attend hospital regularly for either clinic visits or treatment. This problem is further compounded by the fact that lupus is commonly diagnosed in young adulthood, at the time when most patients are either planning on further education or embarking on their career. Many studies have found that patients with lupus often suffer from various detrimental effects on their employment from the disease including higher rates of absenteeism and health-related early retirement. Studies have found that unemployment is up to four times higher in patients with lupus when compared with the general population level.Patients should be encouraged to be open with their employer regarding their diagnosis and this is vitally important if the symptoms of their disease could potentially pose a risk at work (for example in the context of CNS lupus). It is also vital to highlight the highly variable nature of the disease and that flares can often be difficult to predict. Both rheumatologists and rheumatology nurse specialists can support patients with this. In addition, certain jobs may be more challenging following a diagnosis of lupus, for example, if an individual’s job involves a high burden of physical activity or if they are working outside (thus risking significant sun exposure) and role modifications may be necessary.

conclusion

In conclusion, fatigue is a prevalent symptom that conveys significant detrimental effects on quality of life. The impact of disease upon work and exercise are also important to consider. It is essential that there is close communication between primary care and rheumatology specialists, in particular with regard to the management of the impact of lupus on an individual’s lifestyle.Dr Chris Wincup

Prof Anisur Rahman

Department of Rheumatology

Division of Medicine

University College London.

Prof Anisur Rahman

Department of Rheumatology

Division of Medicine

University College London.

©2024 LUPUS UK (Registered charity no. 1200671)

©2024 LUPUS UK (Registered charity no. 1200671)