The Eyes and Lupus

This site is intended for healthcare professionals as a useful source of information on the diagnosis, treatment and support of patients with lupus and related connective tissue diseases.

Introduction

Ocular manifestations of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (lupus) are relatively common but are usually fairly mild. Broadly, they can be divided into those affecting either the front or the back of the eye or as drug effects, particularly those of hydroxychloroquine.A. Front of the eye

(a) Keratoconjunctivitis sicca (dry eyes)

Approximately 30% of lupus patients will have evidence of keratoconjunctivitis sicca (dry eyes). The main symptoms are of gritty, irritable, uncomfortable eyes that may be associated with some redness. Vision is unaffected; there is no pain, photophobia or discharge.

Treatment

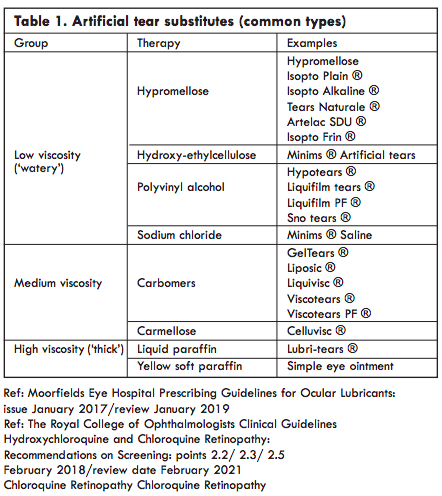

Artificial tear substitutes, instilled as drops or a gel, usually give relief of symptoms. When selecting a treatment the main factor to consider is its viscosity. Low viscosity drops require frequent administration (sometimes more than hourly) but have minimal effect on vision. More viscous gels transiently blur the vision but are longer lasting and so may be effective when used only 4-6x/d. Highly viscous paraffin based ointments significantly blur vision and may only be suitable for night time use.A combination of a gel during the day and a paraffin at night is one popular and effective combination (Table 1).

Patients with more severe keratoconjunctivitis sicca who do not respond to these treatments will need to be referred to an ophthalmologist who will consider using preservative-free preparations, physiological tear substitutes (e.g. the hyaluronic acid based preparations), or even plugging the openings of the tear ducts.

(b) Scleritis

This is an unusual (2.4% of cases) but potentially sight threatening condition and may be an important indication of the severity of the lupus. One or both eyes may be involved and patients complain of pain, often so severe that it wakes them at night. There is an area or areas of intense redness with normal visual acuity and no photophobia or discharge.

Treatment

Mild cases usually require the use of oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Severe cases or cases where treatment has failed will need systemic immunosuppression in the form of oral corticosteroids often with an immunosuppressant and, in resistant cases, pulsed intravenous methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide.

(c) Other manifestations

A red eye in SLE may arise due to more superficial inflammation, such as infective conjunctivitis or episcleritis. Conjunctivitis is usually associated with watery or sticky discharge and the eye or eyes are usually diffusely red. In episcleritis the redness is focal, and there will be minimal discharge. In both cases the eye may feel gritty and uncomfortable but the vision is normal.

Treatment

Conjunctivitis can be treated with a course of antibiotic drops. Episcleritis will often settle down without treatment but may be made more comfortable with ocular lubricants. Oral NSAIDs, such as flurbiprofen or ibuprofen, can be effective but should only be prescribed if there are no contra-indications as a result of the lupus. Topical corticosteroids have a role in resistant cases but should normally only be prescribed under ophthalmic supervision.

Approximately 30% of lupus patients will have evidence of keratoconjunctivitis sicca (dry eyes). The main symptoms are of gritty, irritable, uncomfortable eyes that may be associated with some redness. Vision is unaffected; there is no pain, photophobia or discharge.

Treatment

Artificial tear substitutes, instilled as drops or a gel, usually give relief of symptoms. When selecting a treatment the main factor to consider is its viscosity. Low viscosity drops require frequent administration (sometimes more than hourly) but have minimal effect on vision. More viscous gels transiently blur the vision but are longer lasting and so may be effective when used only 4-6x/d. Highly viscous paraffin based ointments significantly blur vision and may only be suitable for night time use.A combination of a gel during the day and a paraffin at night is one popular and effective combination (Table 1).

Patients with more severe keratoconjunctivitis sicca who do not respond to these treatments will need to be referred to an ophthalmologist who will consider using preservative-free preparations, physiological tear substitutes (e.g. the hyaluronic acid based preparations), or even plugging the openings of the tear ducts.

(b) Scleritis

This is an unusual (2.4% of cases) but potentially sight threatening condition and may be an important indication of the severity of the lupus. One or both eyes may be involved and patients complain of pain, often so severe that it wakes them at night. There is an area or areas of intense redness with normal visual acuity and no photophobia or discharge.

Treatment

Mild cases usually require the use of oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Severe cases or cases where treatment has failed will need systemic immunosuppression in the form of oral corticosteroids often with an immunosuppressant and, in resistant cases, pulsed intravenous methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide.

(c) Other manifestations

A red eye in SLE may arise due to more superficial inflammation, such as infective conjunctivitis or episcleritis. Conjunctivitis is usually associated with watery or sticky discharge and the eye or eyes are usually diffusely red. In episcleritis the redness is focal, and there will be minimal discharge. In both cases the eye may feel gritty and uncomfortable but the vision is normal.

Treatment

Conjunctivitis can be treated with a course of antibiotic drops. Episcleritis will often settle down without treatment but may be made more comfortable with ocular lubricants. Oral NSAIDs, such as flurbiprofen or ibuprofen, can be effective but should only be prescribed if there are no contra-indications as a result of the lupus. Topical corticosteroids have a role in resistant cases but should normally only be prescribed under ophthalmic supervision.

B. Back of the eye

Despite the well-recognised and documented features described below, these manifestations are unusual.(a) Retinal Disease

Retinal findings in lupus may result from several pathophysiological mechanisms, including small vessel vasculitis, large vessel occlusive disease, secondary systemic hypertension, and anaemia. Ocular complications tend to occur in acutely ill patients with active system disease.

i. Lupus retinopathy

Classic findings are cotton wool spots and retinal haemorrhages which may be found in 5 to 15% of patients. This microangiopathy probably results from the vasculitis associated with immune complex deposition in the small vessels. A prospective clinical study revealed that 88% of patients with lupus retinopathy had active systemic disease. Furthermore, lupus patients with retinopathy had a significantly decreased survival compared with lupus patients without retinopathy.Visual loss is uncommon and the patients may be asymptomatic.

Treatment

The retinopathy improves with treatment of the systemic disease.

ii. Retinal vasculitis

A few patients with lupus retinopathy develop a severe retinal vasculitis with possible progression to proliferative retinopathy. The visual prognosis is much worse with more than 50% of affected eyes seeing 6/60 or worse. The underlying process is characterised by diffuse arteriolar occlusion with extensive capillary non-perfusion and retinal neovascularisation may result. This may present as a gradual loss of vision, or sudden loss resulting from a vitreous haemorrhage secondary to the retinal neovascularisation. Tractional retinal detachment may occur. Severe retinopathy is typically associated with active systemic disease and with CNS lupus in particular.

Treatment

Immunosuppression, primarily with corticosteroids, is the mainstay of therapy. Laser photocoagulation for proliferative retinopathy (similar to its use in diabetic retinopathy) is felt to be beneficial. Rarely, surgical intervention is required if the vitreous haemorrhage fails to clear or for retinal detachment.

iii. Large vessel occlusive disease

Branch and central retinal vein or arterial occlusions can occur. Arterial occlusions will result in a more profound, usually permanent, visual loss. Arteriolar, particularly branch, occlusions may form part of the anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome. Although venous occlusions often result in permanent loss, some may recover vision with time.

Retinal ischaemia may be a complication and retinal neovascularisation may result, particularly after central retinal vein occlusion. Symptoms are of sudden, painless loss of vision.

Treatment

The patient should be monitored for any further complications, such as retinal ischaemia and neovascularization, which would require treatment. In addition, the systemic disease must be adequately controlled.

iv. Hypertensive retinopathy

Typical retinal vascular changes can be seen in those patients who are hypertensive but these changes can be mistaken for lupus retinopathy and vice versa. Patients may be asymptomatic but would complain of sudden central visual loss if they developed a complication, such as a branch retinal vein occlusion.

Treatment

The changes often resolve with reduction of the blood pressure.

v. Anaemia

In some cases, peripheral, blotchy intraretinal haemorrhages may reflect anaemia combined with thrombocytopaenia, rather than the vasculitic component of the disease.

Treatment

The changes often resolve with resolution of the anaemia.

(b) Choroidal Disease

Lupus choroidopathy

Occasionally, the choroid (the layer beneath the retina) can be involved. Lupus choroidopathy results in multifocal serous detachments of the retina and underlying retinal pigment epithelium. These types of non-rhegmatogenous detachments (i.e. with no retinal hole) may be difficult to see with a direct ophthalmoscope. Visual loss is variable depending on the extent of macular involvement.

Treatment

The detachments may regress with improved control of the systemic disease.

(c) Neuro-ophthalmological Disease

Neurological complications of lupus are seen in 25 to 75% of patients. Several neuro-ophthalmological manifestations of lupus have been reported, including ischaemic optic neuropathy and retrobulbar neuritis. Ischaemic optic neuropathy presents with sudden visual loss, often associated with an inferior altitudinal field loss. This type of field loss affecting the horizontal meridian easily distinguishes it from more posterior visual pathway field defects which obey the vertical meridian. The optic disc is pale and swollen. A swollen optic disc in lupus may also be secondary to hypertension, central retinal vein occlusion and increased intracranial pressure from intracranial disease.

Retrobulbar neuritis results in a central or paracentral scotoma, red desaturation, pain on ocular movement and a relative afferent pupillary defect. The optic disc appears normal and the condition may be difficult to differentiate from that seen in association with demyelination. There is an association between neuroophthalmological disease and the anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome. Retrochiasmal visual problems, such as transient amaurosis, visual hallucinations and homonymous field defects have all been described.

Treatment

Systemic corticosteroids are the treatment of choice but although a return of vision would be expected with retrobulbar neuritis, it may not occur after ischaemic optic neuropathy.

ALL BACK OF THE EYE PROBLEMS SHOULD BE REFERRED TO AN OPHTHALMOLOGIST

C. Ocular Toxicity and Hydroxychloroquine

Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) is commonly prescribed for the treatment of systemic and cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Although recognized as safe and efficacious, there is a small risk that HCQ can cause toxicity to the retina. This risk, as indicated in the updated Royal College of Ophthalmologists guidelines on HCQ monitoring (RCOphth, 2018), is increased in patients that:

- Take HCQ in excess of 5mg/kg/day;

- Have taken HCQ for more than 5 years; Have impaired renal function (eGFR less than 60 mL/min);

- Take or have taken tamoxifen;

- Have had prior exposure to chloroquine;

- Have, or are found to have at

assessment, existing retinal pathology (for example, dry macular degeneration).

The mechanism of effect is as follows: HCQ binds to melanin in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). This impairs lysosome activity and inhibits phagocytosis of photoreceptor segments shed from the outer photoreceptor layer. These segments accumulate, and the pigment containing cells of the RPE are allowed to filter into the outer layers of the neural retina, migrating concentrically from the fovea and, thereby, causing the classic ‘Bullseye’ sign seen on the macula. Because of the damage caused to the photoreceptors and the RPE, HCQ retinopathy, if allowed to progress, is sight threatening and irreparable.

It is important and reassuring to note that HCQ retinopathy remains uncommon. Nevertheless, recent data gathered from numerous international studies suggest an increase in the prevalence of retinopathy from approximately 5% to 7.5% after five years of treatment, increasing to 20% to 50% after twenty years of treatment. HCQ retinopathy seen within the first five years of treatment remains extremely rare. This rise is partly attributable to the increasingly sophisticated screening modalities employed in the modern ophthalmic setting. At its earliest stages, the patient with HCQ retinopathy will be visually asymptomatic. Commonly employed screening tools utilised in primary care settings, such as an Amsler grid, or an Ishihara test to assess for depreciation of colour vision, are not sufficiently sensitive to identify early onset retinopathy. By the time the patient is alert to visual symptoms such as blurring of vision, diminished colour sensitivity, metamorphopsia and scotoma, the retina has already been significantly affected.

The updated RCOphth guidelines recognise the recorded rise in prevalence, and the increasing sensitivity of screening modalities. It, therefore, advises that all patients newly initiated on hydroxychloroquine are to be referred to the hospital eye service for a baseline ophthalmic assessment within a maximum of 12 months from commencement. The assessment must include a Humphrey 10-2 visual field test, SD-OCT of the maculae, and wide field imaging of the retinae as paramacular presentation of hydroxychloroquine retinopathy is an uncommon but recognised phenomenon, particularly among the south-east Asian population.

If the baseline assessment is satisfactory, and the patient does not present with any of the risk factors described above, they are discharged from the hospital eye service with the expectation that they are referred again for annual assessment if they remain on HCQ after five years. It should be clearly articulated to the patient that in the interim period they continue to see their optician on an annual basis for routine eye health checks.

Should the patient meet one of the risk factors described above, or if there is something incidentally seen on assessment but unrelated to hydroxychloroquine, then they will be kept under annual review. The patient will be asked to continue with their HCQ as instructed, and the prescribing clinician will be informed of the findings. If a patient presents with advanced macular or para-macular change, then as their presence prohibits the early detection of HCQ retinopathy, the advice to the prescriber should be that HCQ is stopped and an alternative agent prescribed if possible.

All patients who have taken HCQ for 5 years or more should receive annual screening. Any patient who has taken chloroquine for more than one year should also receive annual screening.

Lastly, HCQ retinopathy is classified in one of three ways: no toxicity, possible toxicity and definite toxicity. All patients with no toxicity are safe to continue with their medication and are reviewed as per guidelines. Any patient who presents with possible toxicity (where one test result is typical of HCQ retinopathy) should continue with their HCQ. If the abnormal test is on SD-OCT but not visual field testing, then the patient should be seen annually. Should the visual field test show an abnormality then it ought to be repeated to ascertain if the defect is reproducible, and if it is, then the patient needs to be referred for multifocal electroretinography (mERG). HCQ should be continued until the result of the mERG is known. Where identified, it is recommended to the prescriber that a patient with definite toxicity (where two test results are typical of HCQ retinopathy) should stop HCQ. A description of the severity of toxicity should be included to aid clinical decision making on the part of the prescriber. Although the ophthalmologist can recommend cessation of HCQ in light of findings suggestive of retinopathy, the final decision to do so rests with the prescribing clinician.

- Take HCQ in excess of 5mg/kg/day;

- Have taken HCQ for more than 5 years; Have impaired renal function (eGFR less than 60 mL/min);

- Take or have taken tamoxifen;

- Have had prior exposure to chloroquine;

- Have, or are found to have at

assessment, existing retinal pathology (for example, dry macular degeneration).

The mechanism of effect is as follows: HCQ binds to melanin in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). This impairs lysosome activity and inhibits phagocytosis of photoreceptor segments shed from the outer photoreceptor layer. These segments accumulate, and the pigment containing cells of the RPE are allowed to filter into the outer layers of the neural retina, migrating concentrically from the fovea and, thereby, causing the classic ‘Bullseye’ sign seen on the macula. Because of the damage caused to the photoreceptors and the RPE, HCQ retinopathy, if allowed to progress, is sight threatening and irreparable.

It is important and reassuring to note that HCQ retinopathy remains uncommon. Nevertheless, recent data gathered from numerous international studies suggest an increase in the prevalence of retinopathy from approximately 5% to 7.5% after five years of treatment, increasing to 20% to 50% after twenty years of treatment. HCQ retinopathy seen within the first five years of treatment remains extremely rare. This rise is partly attributable to the increasingly sophisticated screening modalities employed in the modern ophthalmic setting. At its earliest stages, the patient with HCQ retinopathy will be visually asymptomatic. Commonly employed screening tools utilised in primary care settings, such as an Amsler grid, or an Ishihara test to assess for depreciation of colour vision, are not sufficiently sensitive to identify early onset retinopathy. By the time the patient is alert to visual symptoms such as blurring of vision, diminished colour sensitivity, metamorphopsia and scotoma, the retina has already been significantly affected.

The updated RCOphth guidelines recognise the recorded rise in prevalence, and the increasing sensitivity of screening modalities. It, therefore, advises that all patients newly initiated on hydroxychloroquine are to be referred to the hospital eye service for a baseline ophthalmic assessment within a maximum of 12 months from commencement. The assessment must include a Humphrey 10-2 visual field test, SD-OCT of the maculae, and wide field imaging of the retinae as paramacular presentation of hydroxychloroquine retinopathy is an uncommon but recognised phenomenon, particularly among the south-east Asian population.

If the baseline assessment is satisfactory, and the patient does not present with any of the risk factors described above, they are discharged from the hospital eye service with the expectation that they are referred again for annual assessment if they remain on HCQ after five years. It should be clearly articulated to the patient that in the interim period they continue to see their optician on an annual basis for routine eye health checks.

Should the patient meet one of the risk factors described above, or if there is something incidentally seen on assessment but unrelated to hydroxychloroquine, then they will be kept under annual review. The patient will be asked to continue with their HCQ as instructed, and the prescribing clinician will be informed of the findings. If a patient presents with advanced macular or para-macular change, then as their presence prohibits the early detection of HCQ retinopathy, the advice to the prescriber should be that HCQ is stopped and an alternative agent prescribed if possible.

All patients who have taken HCQ for 5 years or more should receive annual screening. Any patient who has taken chloroquine for more than one year should also receive annual screening.

Lastly, HCQ retinopathy is classified in one of three ways: no toxicity, possible toxicity and definite toxicity. All patients with no toxicity are safe to continue with their medication and are reviewed as per guidelines. Any patient who presents with possible toxicity (where one test result is typical of HCQ retinopathy) should continue with their HCQ. If the abnormal test is on SD-OCT but not visual field testing, then the patient should be seen annually. Should the visual field test show an abnormality then it ought to be repeated to ascertain if the defect is reproducible, and if it is, then the patient needs to be referred for multifocal electroretinography (mERG). HCQ should be continued until the result of the mERG is known. Where identified, it is recommended to the prescriber that a patient with definite toxicity (where two test results are typical of HCQ retinopathy) should stop HCQ. A description of the severity of toxicity should be included to aid clinical decision making on the part of the prescriber. Although the ophthalmologist can recommend cessation of HCQ in light of findings suggestive of retinopathy, the final decision to do so rests with the prescribing clinician.

Dr Xiaoxuan Liu

Ophthalmology Research Fellow

Prof Alastair Denniston

Consultant Ophthalmologist

Department of Ophthalmology

University Hospitals Birmingham NHSFT

Ophthalmology Research Fellow

Prof Alastair Denniston

Consultant Ophthalmologist

Department of Ophthalmology

University Hospitals Birmingham NHSFT

Mr Robert Carmichael

Nurse Specialist for Inflammatory Eye Disease

Nurse Specialist for Inflammatory Eye Disease

©2024 LUPUS UK (Registered charity no. 1200671)

©2024 LUPUS UK (Registered charity no. 1200671)