The Kidneys and Lupus

This site is intended for healthcare professionals as a useful source of information on the diagnosis, treatment and support of patients with lupus and related connective tissue diseases.

Introduction

The overall survival of patients with lupus has improved considerably over the last few decades, from a 75% 5 year survival in the 1950s to a >90% 10 year survival in 2000; however, lupus nephritis and associated end-stage renal disease is associated with at least a 2-fold higher risk of mortality. Early deaths from extra renal lupus and infection are now uncommon but, instead, renal failure and cardiovascular disease have emerged as important determinants of morbidity and mortality. The risk of developing end stage renal disease from lupus nephritis decreased steadily world-wide in the last three decades of the twentieth century, to a 17% 10-year risk and a 22% 15-year risk in the mid-1990’s. This may be attributable to a number of factors, including better immunosuppressive regimens, antihypertensive drugs and supportive care. From 2000 onwards this pattern of improvement appears to have plateaued, emphasising the importance of ongoing research into effective management strategies.Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of lupus in general, and lupus nephritis in particular, is complex and multifactorial and is discussed in more detail elsewhere in this book. Key to the pathogenesis of renal disease is the deposition/in situ formation of glomerular immune complex (containing immunoglobulin and complement components). This can be visualised by immune-staining or electron microscopy of renal biopsy tissue. Localisation of immune complex is an important classification feature in lupus nephritis (see below) and largely correlates with renal disease phenotypes.Clinical phenotypes

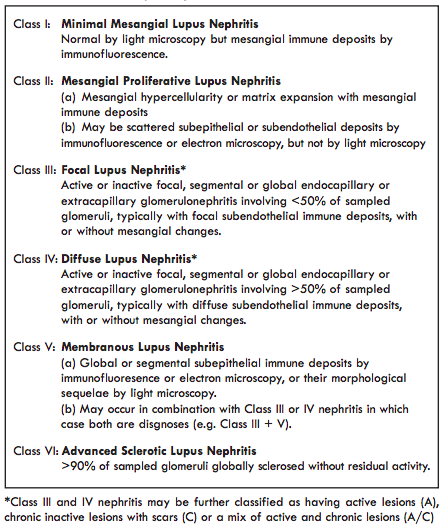

The American College of Rheumatology 1982/1997 lupus classification criteria were re-visited by the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) group in 2012. From a renal perspective the key change in these criteria was the recognition of isolated renal disease as a manifestation of SLE. A kidney biopsy consistent with lupus nephritis in an individual positive for Antinuclear Antibodies is considered to be classifiable lupus.Lupus nephritis is classified based on histological appearances at renal biopsy using the International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society (ISN/RPS) 2003 classification, 2017 (Table 1).

Lupus Nephritis - Renal Presentations

The kidney is the internal organ most commonly affected in lupus, with clinically apparent nephritis developing in 40 75 % of patients. Nephritis typically develops early in the course of lupus and in most patients lupus nephritis will have appeared within 5 years of diagnosis. In many patients, renal disease is asymptomatic and identified by the presence of proteinuria +/- haematuria, but some patients present with ‘nephrotic syndrome’ (heavy proteinuria, hypoalbuminaemia and peripheral oedema). Renal function at presentation may be normal or reduced, but rapid deterioration in kidney function is uncommon. The presence of either renal dysfunction or heavy proteinuria is prognostically important and warrants urgent investigation. Renal dysfunction without proteinuria is rare in active lupus nephritis and is more likely to indicate kidney disease due to other causes.Assessment of blood pressure is central to the evaluation of patients with suspected or confirmed lupus nephritis. Severe hypertension requires urgent intervention.

Lupus nephritis will often present in patients with evident Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, with extra-renal symptoms such as a rash, arthralgia, Raynaud's phenomenon and pleuro pericarditis. Other patients will have no extra-renal disease or will only develop extra-renal signs of lupus after a period of months to years.

Investigations in Lupus Nephritis

Laboratory testsPatients with active lupus nephritis commonly have markers of systemic disease on their non-renal blood tests. Haematological tests can show leucopenia, lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia, often in association with an anaemia of chronic disease. Patients may have raised polyclonal immunoglobulin concentrations but identification of a monoclonal paraprotein or other significant haematological abnormality may require further investigation, particularly as haematological malignancies and paraprotein-related renal disease are important differential diagnoses in patients with lupus-like renal disease. C reactive protein (CRP) is classically not raised in active lupus, unless disease exacerbation is accompanied by serositis or infection. However, exceptions to this are frequently observed and a raised CRP should certainly not be used to discount lupus as a diagnosis. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is often raised but is of limited overall diagnostic role.

All patients with suspected or diagnosed lupus should have their urine tested for protein and blood at each clinic visit as this is the key modality for identifying new or flaring renal disease. Twenty-four hour urine collections for urinary protein quantification are still utilised in clinical trials but in clinical practice assessment of the albumin or protein: creatinine ratio from a spot urine sample is more practicable. The presence of an ‘active urinary sediment’ (dysmorphic red cell or red cell casts on microscopy) is traditionally considered to be indicative of active nephritis, however, trial data demonstrate that haematuria does not improve or provide additional prognostic information beyond that provided by renal function and proteinuria in lupus nephritis. Additionally, most hospitals have now moved to automated urinalysis by flow-cytometry so the expertise/facilities to perform microscopy have largely disappeared. Renal function should be assessed by estimation of glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Serum creatinine is influenced by sex and muscle and, therefore, may appear to be within the normal range in patients with significant renal disease. Impaired renal function at presentation indicates significant underlying renal involvement and is an adverse prognostic factor predicting subsequent development of chronic kidney disease.

Immunology

Patients with lupus nephritis frequently have immunological test results indicating lupus activity (rising dsDNA antibody levels in patients that are dsDNA antibody positive and falling compliment levels).Antiphospholipid syndrome (anticardiolipin/β2-Glycoprotein1 antibodies and/or a positive lupus anticoagulant in a patient with thrombosis or recurrent miscarriage) is relevant to patients with renal disease as thrombotic microangiopathy or renal vein thrombosis may lead to rapid renal dysfunction but would be managed through anticoagulation rather than immunosuppression (unless concurrent nephritis or extra-renal lupus).

Role of renal biopsy

A renal biopsy should ordinarily be performed in all patients with evidence of newly presenting glomerular disease. Initial biopsy confirms diagnosis and is indicative of baseline activity versus chronicity (damage). Repeat renal biopsy is useful in the context of a decline in renal function, increasing proteinuria or nonremission after induction therapy, in order to differentiate between active disease (flare or refractory nephritis) and irreversible damage.Prior to undertaking a biopsy, kidneys should be imaged by ultrasound to confirm normal size (usually >10cm bipolar length in adults) and to exclude hydronephrosis and other anatomical abnormalities. Urinary infection should be excluded or treated prior to performing a renal biopsy. Blood pressure should be adequately controlled before undertaking a renal biopsy. Unless there are contra-indications, we would typically biopsy patients with an albumin:creatinine ratio >30mg/mmol or renal dysfunction who do not have a prior histological diagnosis. Histology provides a basis for therapeutic options as well as providing prognostic information. Ongoing multi-disciplinary collaboration, particularly between rheumatologists and nephrologists, is essential to providing high quality care for patients with lupus nephritis.

Monitoring disease activity

Urinalysis and quantification of proteinuria by urinary ACR or PCR where dipstick proteinuria is detected, should be performed at each clinic visit for all patients with SLE. Quantified proteinuria and renal function, assessed by serum creatinine and eGFR, should be monitored serially in patients with known or previous lupus nephritis. The frequency of monitoring should reflect the severity of disease, with patients who exhibit deteriorating renal function or who are nephrotic requiring close observation. The persistence or re emergence of proteinuria (+/- haematuria) indicate renal disease and warrant further evaluation to differentiate active nephritis from chronic kidney disease. Disease monitoring should also include an assessment of extra-renal clinical symptoms and include other blood tests such full blood count, complement levels and dsDNA antibodies as discussed elsewhere in this book.Approach to the therapy of lupus nephritis

The same drugs that are used to manage systemic lupus are employed in lupus nephritis. Drug regimens are increased in response to flares and gradually tapered during periods of remission. High dose corticosteroids and potent immunosuppressive drugs are reserved for patients with life threatening manifestations including severe lupus nephritis, central nervous system, cardiopulmonary disease or haematological abnormalities such as thrombocytopenia.A number of factors need to be considered when planning treatment for patients with lupus nephritis. Firstly, the choice of initial immunosuppressive regimen should typically reflect clinical presentation (e.g. nephrotic syndrome or impaired renal function), histological classification, whether it is de novo, relapsed or refractory nephritis and factors related to patients’ preferences including reproductive health and anticipated concordance. The presence of extra-renal manifestations of lupus is also relevant although, in many cases, immunosuppression for nephritis will also control extra-renal disease. A number of randomised controlled trials have been published over the last 10 years which have helped us develop a more standardised approach. The second consideration is the use of appropriate longerterm immunosuppression to maintain disease remission in patients responding to the initial regimen. Thirdly, it is important to consider adjunctive treatments in renal disease, in particular, measures to control blood pressure, limit urine protein leak, provide supportive management of chronic kidney disease and, if necessary, to plan for approaching end-stage kidney disease.

These treatment considerations have been synthesised into three clinical practise guidelines published in 2012 by the American College of Rheumatology, the European League against Rheumatism and the Kidney Diseases Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Group. These guidance documents are highly concordant with some subtle differences in emphasis. The following sections are largely drawn from these documents and the primary sources of data as well as advice from our personal practice.

Treatment of ISN/RPS Class I and II Nephritis

Patients with class I or II lupus nephritis generally have low level proteinuria and preserved renal function and, consequently, do not undergo renal biopsy. Where class I or II lupus nephritis is confirmed, the risk of progressive kidney disease is very low and background immunosuppression beyond that required for extrarenal lupus is, in general, not warranted. Occasionally, reducing courses of lowerdose steroids or lower levels of other immunosuppression (azathioprine or mycophenolate) are used in class II nephritis but there is no trial evidence to support management decisions. Rarely, patients with lupus develop nephrotic syndrome associated with a ‘podocytopathy’ (analogous to minimal change nephropathy) which falls outside of the ISN/RPS classification but can be treated with tapering high dose steroids. The risk of subsequent development of more significant renal disease should also be considered in patients with class I or II lupus nephritis and re-biopsy should be considered where worsening proteinuria or renal dysfunction arise.Treatment of ISN/RPS Class III and IV Lupus Nephritis

Mycophenolate mofetil (2-3g/day) is generally used as the first line induction therapy for patients with a Class III/IV nephritis. An alternative approach is intravenous cyclophosphamide given as a regimen of 6 x 500mg fixed dose pulses given every two weeks. Lower dose cyclophosphamide exposure given in this regimen may reduce the risk of serious infection and available evidence suggests it does not impact fertility in younger women, however, the convenience of oral dosing and the absence of gonadal toxicity mean that mycophenolate tends to be utilised as first line therapy in most patients. Cyclophosphamide is typically reserved for patients who fail to respond or who have significant extra-renal disease for which mycophenolate is felt to be insufficient (e.g. cerebral lupus). Intravenous cyclophosphamide may also be advantageous for patients with severe nephrotic syndrome in whom absorption of oral medication can be impaired and in patients with very aggressive renal disease (‘rapidly progressive’) with necrotising glomerulonephritis although other approaches, including use of rituximab (see below), are also considered effective by some experts.The use of rituximab (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) remains an area of debate. The 2012 LUNAR study failed to meet its primary study endpoint of superior efficacy of rituximab over standard treatment regimens but the argument has been made that study design considerations, in particular related to concomitant steroid usage, may have clouded the true benefit of rituximab. Numerous smaller studies and registry data have indicated that for many patients rituximab is an effective treatment option. At the time of writing, the NHS in the UK only permits use of rituximab in patients with refractory nephritis and the authors tend to use this as a second line treatment option if mycophenolate fails.

Standard induction treatment regimens include initial high-dose steroids that may include initial intravenous methylprednisolone pulses or oral prednisolone at 0.5-1.0 mg/kg tapered steadily over a few weeks. It is increasingly realised that the high life time steroid burden of many patients with lupus may actually contribute to morbidity, both in terms of infection risk and in terms of ‘organ damage’ (medical events such as myocardial infarction and diabetes that have lasting or long-term implication to ongoing health irrespective of underlying lupus disease activity). Interest is, therefore, increasingly focussed on using medication in a way that minimises traditional reliance on steroids. An extended open label cohort study from Imperial College published in 2013 suggested remission of lupus nephritis could often be effectively achieved with a combination of mycophenolate, rituximab and initial i.v. pulses of steroid but without any prolonged maintenance steroid. Unfortunately, a subsequent randomised study of this regimen was discontinued due to slow recruitment and the NHS in England does not currently fund rituximab as a first line treatment so access to this regimen is restricted.

Maintenance therapy in Class III/IV nephritis typically consists of ongoing therapy with mycophenolate or azathioprine. Randomised controlled trials have produced differing findings on the relative efficacy of mycophenolate and azathioprine in maintenance, but many patients with nephritis start and continue mycophenolate as run-through induction and maintenance. Azathioprine is useful for patients with mycophenolate intolerance, or female patients on maintenance therapy who wish to become pregnant.

There is very little data to guide the duration of maintenance therapy, but data from individual centres show that treatment withdrawal is eventually possible in a good proportion of patients. Our personal approach in patients with a single episode of nephritis that responds well to induction therapy and without extra-renal considerations is to attempt steroid withdrawal at about 2 years, and immunosuppression withdrawal at 5 years, continuing hydroxychloroquine longer-term. In patients with a history of relapse we adopt a much more cautious approach.

Treatment of ISN/RPS Class V Nephropathy.

By comparison with class III or IV lupus nephritis, pure class V (membranous) lupus nephritis is less common (~15% of patients with LN undergoing biopsy). Histologically features of more than one class can co-exist (class V+III or V+IV). Typically, patients with pure class V lupus nephritis have heavier proteinuria or nephrotic syndrome and preserved renal function. The authors’ experience is that serological markers of lupus activity (high titre dsDNA antibodies or low complement levels) may be absent in patients in class V nephritis. Guidelines and the authors’ preference would generally be to treat Class V nephritis with mycophenolate in a similar way to Class III/IV nephritis. In patients with disease refractory to mycophenolate and rituximab, we tend to revert to low-dose cyclophosphamide, although recognising that there is little trial evidence for efficacy in this sub-group. Calcineurin inhibitors (CNI’s - tacrolimus or ciclosporin) can also be effective in controlling proteinuria but in the authors’ opinion should be primarily used in patients with normal renal function and for a limited period of time (2-4 years) given that longer term exposure to these agents is recognised to promote renal fibrosis. Use of CNIs in lupus nephritis is supported by their efficacy in idiopathic membranous nephropathy and by lupus nephritis trial evidence (see medication section below).The presence of renal impairment at presentation is generally lower in pure class V than class III or IV lupus nephritis. Patients with pure class V who are not nephrotic or do not have nephrotic range proteinuria appear to have a good longer term prognosis, but the risk of progressive renal impairment in Class V lupus nephritis is still significant in those with nephrotic syndrome who fail to remit. The presence of concurrent class III or IV at initial biopsy or as an emergent feature in patients who originally had class V nephritis which flares after treatment or fails to remit, may also impact prognosis.

Strict blood pressure control using Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitor (ACEI) or Angiotensin Receptor Blocker (ARB) drugs are important components of the effective management of proteinuria in class V lupus nephritis. Prophylactic anticoagulation should be considered in patients with significant hypoalbuminaemia.

Treatment of ISN/RPS Class VI nephritis

This class of nephritis is defined by advanced scarring with no evidence of inflammatory disease activity. Management is through supportive therapy for chronic kidney disease and there is no role for additional immunosuppression unless required for extra-renal disease. Consideration may be given to withdrawal of maintenance immunosuppression if clinically appropriate.Other therapeutic considerations

The various drugs used in the treatment of lupus are discussed elsewhere in this book See chapter - Drug Therapy of LupusThese additional notes are applicable to additional treatment considerations specifically in lupus nephritis.

Hydroxychloroquine

Although hydroxychloroquine is insufficient, as monotherapy, to manage Class III, IV and V nephritis, it is recommended as an adjunctive treatment for all patients based on evidence it may reduce lupus flare rate, reduce overall damage accrual and, perhaps, reduce the risk of thrombotic events.Mycophenolic Acid

Some patients appear to find enteric coated mycophenolate sodium causes less gastrointestinal side effects than my cophenolate mofetil. Although not tested directly in lupus, or in head-to-head comparisons, we generally regard 320mg of mycophenolate sodium to be equivalent to 500mg mycophenolate mofetil.Renin-angiotensin blockade

All patients with significant proteinuria (ACR more than 30 mg per mmol) should be treated with either angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs). These drugs reduce urinary protein leak through a direct effect on glomerular haemodynamics and exert an anti fibrotic effect. In proteinuric patients, blood pressure should ordinarily be treated to less than 130 / 80. Evidence from chronic kidney disease in general shows that reducing protein leak and treatment with ACEI or ARB drugs has a beneficial effect on long term kidney function and reduces adverse outcomes. These drugs should not be initiated during acute kidney injury (caused by lupus or other reasons) and should be paused if further acute kidney injury occurs. Alternative anti-hypertensive agents may be required in the setting of acute kidney injury.Calcineurin Inhibitors

There are a number of trials looking at the calcineurin inhibitors (ciclosporin or tacrolimus) used as monotherapy or in combination with mycophenolate mofetil for induction or maintenance therapy in lupus nephritis. The data primarily derive from studies in China that utilised a ‘multi-drug’ therapy combining tacrolimus, mycophenolate and steroids in patients with class III, IV, V or V+III or V+IV nephritis. These studies do support efficacy, although longer-term data are limited and the longerterm nephrotoxicity and adverse effect on blood pressure are a concern.Leflunomide

There is a small amount of open-label data to support the efficacy of leflunomide in lupus nephritis. It may be a fall-back option in patients with multiple drug intolerances or where other options have failed but there is insufficient evidence to support anything more than occasional usage.Belimumab

Belimumab is a human monoclonal antibody targeting BLyS/BAFF (a B-cell proliferation and maturation factor). It is licensed and approved for use in the US and Europe and is available for use in the NHS provided stringent criteria are met and disease activity is high. Patients with active lupus were excluded from initial belimumab trials so there is currently insufficient data to recommend usage in lupus nephritis. Nonetheless, a post-hoc analysis of belimumab trials focussing on patients who had evidence of nephritis (proteinuria) showed a trend to improvement in renal parameters. Renal trials are in progress.Methotrexate

Methotrexate may be useful as a steroid sparing agent in lupus with arthritis and serositis and may have potential benefits in mild nephritis. Methotrexate is, however, renally excreted and cannot be used in patients with renal impairment (eGFR less than 30ml/min), therefore, it has no real role in the treatment of lupus nephritis.Plasmapheresis

There is no evidence to support the use of plasmapheresis in lupus nephritis. It may be used in patients with concomitant catastrophic anti phospholipid syndrome/thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura or, occasionally, as a ‘last-ditch’ measure in a critical treatment-refractory scenario.Intravenous immunoglobulins

Uncontrolled studies have shown a temporary benefit in lupus patients from the infusion of high doses of intravenous immunoglobulin but there is insufficient evidence to support use. IVIG usage guidelines generally precludes use on the NHS but, occasionally, it may have a role in patients with concomitant sepsis and high disease activity.General measures

Patients whose lupus nephritis leads to chronic kidney disease (persistent renal dysfunction or proteinuria) should receive supportive management in line with chronic kidney disease in general. This includes careful management of blood pressure (target less than 130 / 80) and cholesterol lowering therapy. All patients with lupus nephritis, including those with chronic kidney disease, require ongoing nephrology input, including for management of mineral bone disease and anaemia in more advanced CKD. Patients with lupus nephritis require a significant level of immunosuppression and often have a legacy of treatment with multiple agents and prolonged therapy, so efforts to reduce infection risk are important. We recommend annual influenza vaccination and 5 yearly pneumococcal vaccination. We monitor general immunoglobulin levels and, in selected patients, functional antibody levels against vaccinatable disease to provide rationale for booster vaccination. Although we recognise that patients with lupus have a higher rate of adverse reaction to co-trimoxazole we also feel this is a particularly high-risk population and in patients receiving cyclophosphamide or rituximab/mycophenolate combinations, we feel the benefits of Pneumocystis prophylaxis with cotrimoxazole outweigh the risks.Prognostic factors in lupus nephritis

Knowledge about prognosis assists physicians in their choice of treatment and provides patients with information on the possible outcomes. Understanding which factors in early disease predict poor long-term outcomes (chronic kidney disease or end-stage renal disease) is an important question but challenging to answer given the time typically taken for progressive disease to develop. Patients with proliferative glomerulonephritis (ISN/RPS Class III/IV) tend to have a worse outcome for renal function when compared to patients with milder lesions. Patients who present with significant kidney dysfunction or with chronic histological changes at the outset have a higher risk of progressive disease. Patients from non-European ethnicity also appear to have worse prognosis.Increasing evidence suggests that the presence of persistent proteinuria is an important marker of poor prognosis. We know that the resolution of proteinuria following treatment for new lupus nephritis can take some months, but there is evidence that patients in whom proteinuria has normalised (or reduced to less than 0.7g / 24 hours) by 12 months have a better prognosis than patients with persistent proteinuria. Repeated nephritis relapses increase risk of chronic kidney disease progression.

Dialysis and Transplantation

Around 15-20% of patients with lupus nephritis develop end-stage renal failure by 10-15 years. Both haemodialysis and continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis are suitable options for patients with lupus and there is tendency for lupus disease activity to diminish after the start of dialysis. If there is no overt disease activity, immunosuppressants in patients on dialysis are generally discontinued. Overall survival on dialysis is good with a 75% survival at 10 years. For appropriately selected patients with end-stage renal disease of any cause transplantation is the optimal method of renal replacement therapy (offering superior quality of life and survival compared with dialysis). Pre-emptive transplantation offers the best outcome of all and pre-emptive transplant listing should be the aim for all suitable patients. In most patients with lupus nephritis, endstage renal disease arises through progressive CKD remote from active lupus nephritis and pre-emptive transplantation is an entirely appropriate option which should be proactively discussed and promoted. For the uncommon subset of patients who progress to ESRD in the context of active and recently diagnosed lupus nephritis, timing of transplant work-up and listing requires expert evaluation and might need to be temporarily deferred. Graft survival and function in patients with lupus after transplantation are comparable to those obtained in patients with other diseases. Recurrence of lupus nephritis is uncommon, but not unheard of, after transplantation. Renal transplantation also offers the potential to restore or improve fertility in women with advanced CKD or ESRD.Conclusion

Any lupus patient with symptoms of renal involvement must be referred to a specialist so that the diagnosis can be established, disease severity assessed and a management plan formulated. Immunosuppressive therapy and corticosteroids have, undoubtedly, had an impact on renal preservation in patients with severe lupus nephritis, however, many patients still have refractory or relapsing disease that leads to chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease requiring renal replacement therapy.Both the hospital physicians and general practitioners have a very important role to play in the management of these patients, especially in monitoring drug toxicity, blood pressure and renal function. Regular clinical review of the patient’s condition, together with laboratory tests and urinalysis to detect marrow depression, disease activity or progressive disease is mandatory in the management of these patients.

Table 1 - The International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society 2003 Classification of Lupus Nephritis

Dr Ben Rhodes

Consultant Rheumatologist

Queen Elizabeth Hospital

Edgbaston

Birmingham B15 2TH

Consultant Rheumatologist

Queen Elizabeth Hospital

Edgbaston

Birmingham B15 2TH

Dr Peter Hewins

Consultant Nephrologist

Consultant Nephrologist

©2024 LUPUS UK (Registered charity no. 1200671)

©2024 LUPUS UK (Registered charity no. 1200671)